The Chapel of Queen Theodolinda opens in the northern arm of the transept of Monza Cathedral. Its pictorial decoration, dating from the mid-15th century and dedicated to the Stories of Theodolinda, distributed in 45 scenes, stands as the most

The Chapel of Queen Theodolinda opens in the northern arm of the transept of Monza Cathedral. Of slender Gothic forms, it was erected in the years at the turn of the 1400s, during the last phase of the basilica's reconstruction work begun in the 1300s. Its pictorial decoration, dating from the mid-15th century and dedicated to the Stories of Theodolinda, distributed in 45 scenes, is presented as a heartfelt tribute to the Lombard sovereign who had founded the church and at the same time as a testimony to the delicate dynastic transition that was then looming in the Duchy of Milan between the Visconti family and that of the Sforza, to which the heraldic symbols painted in the frames and the metaphorical allusions to the marriage between Bianca Maria Visconti and Francesco Sforza in the images refer.

With the surviving works of Michelino da Besozzo, Pisanello and Bonifacio Bembo, to whom it is intimately related stylistically, the chapel's fresco cycle is considered one of the masterpieces of international Gothic painting in Italy, as well as the most important outcome of the activity of the Zavattari: a family of Milanese painters active in Lombardy throughout the 15th century, which is presented to us by the documents as a true dynasty of artists, consisting of the progenitor Cristoforo, responsible between 1404 and 1409 for some works in the cathedral in Milan, his son Franceschino, also active in the cathedral in Milan from 1417 to 1453, and the latter's three sons, Giovanni, Gregorio and Ambrogio, with whom Franceschino probably worked in Monza and, with the last two alone, at the Certosa in Pavia. The series is concluded by Franceschino II, son of Giovanni and brother of Vincenzo, Gian Giacomo and Guidone. The chapel was painted on two occasions between 1441-44 and 1444-46 and, in all probability, by four different "hands," which some scholars propose to identify with as many members of the Zavattari family. Scene 32, on which the signature and date 1444 appear, is believed by some to be not only one of the poetic peaks of the cycle but also the junction point between the first and second painting campaigns, as recent archival findings would also attest.

The 45 scenes tell the story of Queen Theodolinda from the historical accounts of Paul Deacon (8th cent.), author of the Historia Langobardorum, and Bonincontro Morigia (14th cent.), author of the Chronicon Modoetiense. Developed over an area of about 500 sq. m. and organized in five overlapping registers, the narrative follows a horizontal course from left to right, and from top to bottom, and is divided as follows: scenes 1 to 23 describe the foreplay and wedding between Theodolinda, princess of Bavaria, and Autari, king of the Lombards, concluding with the king's death; scenes 24 to 30 depict the foreplay and wedding between the queen and her second husband Agilulf; from scene 31 to 41 the foundation and initial events of the Basilica of Monza are depicted, followed by the death of King Agilulfo and the Queen; finally, from scene 41 to 45 the ill-fated attempt to reconquer Italy by the Eastern Emperor Constant and his sad return to Byzantium are illustrated. As the scenes unfold, the pace of the narrative becomes slower or tighter depending on the importance of the moments narrated. As many as 28 stages of the narrative are also devoted to wedding scenes, relating to the queen's two marriages: a circumstance that leads one to believe that the paintings were also designed as a tribute to Bianca Maria Visconti, based on the analogy linking the Lombard queen to the Lombard duchess, who married Francesco Sforza in 1441, thus legitimizing her aspiration to succeed Filippo Maria Visconti in the ducal dignity of Milan. There are many scenes involving court life-dances, feasts, banquets, hunting parties-but also travels and battles, and numerous details on the fashion and costumes of the time presented by the protagonists: clothes, hairstyles, weapons and armor, furnishings, attitudes and attitudes. All of this provides one of the richest and most extraordinary insights into the condition and life at court in 15th-century Milan, perhaps the most European environment in Italy at the time.

The complex process used by the authors - in which such diverse materials and techniques as fresco, dry tempera, relief pastille, gilding and leaf silvering coexist - shows the workshop's extraordinary operational versatility and responds perfectly to the sumptuous climate that dominated in the courts and among the aristocracy of the time. The altar in the Chapel, built in 1895-96 in neo-Gothic style to a design by Luca Beltrami, holds the Iron Crown, the most famous and sacred of the goldsmiths in the Monza Cathedral Treasury.(source: Museo del Duomo)

LA CORONA FERREA

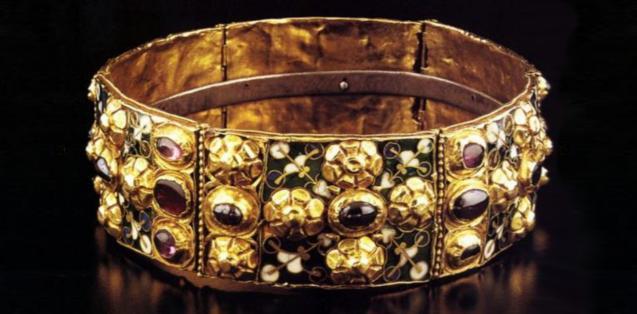

In the altar of the Chapel of Theodolinda is kept the Iron Crown, one of the most important and dense products of goldsmithing in the entire history of the West.

The Iron Crown has been miraculously preserved from the Middle Ages to the present day; it consists of six gold plates - adorned with relief rosettes, bezels of gems and enamels - bearing within it a circle of metal, from which it takes its name "ferrea," which an ancient tradition, reported as early as the late 4th century by St. Ambrose, identifies with one of the nails used in the crucifixion of Christ: a reliquary, then, which St. Helena is said to have found in 326 during a trip to Palestine and inserted into the diadem of her son, Emperor Constantine.

The tradition, which links the Crown to the Passion of Christ and the first Christian emperor, explains the symbolic value attributed to it by the king of Italy(or would-be kings, such as the Viscontis), who would use it in coronations to attest to the divine origin of their power and their connection to the Roman emperors. Recent scientific investigations raise the prospect that the Crown, which as it stands derives from interventions made between the 4th-5th centuries, may be a late-antique royal insignia, perhaps Ostrogothic, passed to the Lombard kings and finally reached the Carolingian sovereigns, who would have it restored and donated to Monza Cathedral.

Since then the history of the tiara was inextricably linked to that of the cathedral and the city. In 1354, for example, Pope Innocent VI sanctioned as an undisputed-though later disregarded-right of Monza Cathedral to be able to host the coronations of the kings of Italy, while in 1576 St. Charles Borromeo instituted the cult of the Sacred Nail there, so as both to make official the recognition of the diadem as a relic, as well as to link it to another Holy Nail, preserved in Milan Cathedral, which according to the same ancient tradition St. Helena is said to have had forged in the shape of a bit for Constantine's horse, as a further metaphor for divine inspiration in the leadership of the Empire.

By virtue of its sacred value, the Iron Crown is preserved in a consecrated altar dedicated to it, erected by Luca Beltrami in 1895-96.

(source: Museo del Duomo)

.